FAQ

This Q&A is based on Dr. Julian Jaursch and Dr. Philipp Lorenz-Spreen’s original published in August 2023; last updated in November 2024, that is accessible here.

It has been edited and expanded by Sophia Graf and LK Seiling; last updated in July 2025.

Abbreviations

Throughout this Q&A, you will come across some abbreviations. We have compiled an overview over the most common ones below

- DSA: Digital Services Act, EU law applying to online platforms throughout the EU

- DDA: Draft Delegated Act on Data Access, published by the Commission for public consultation on 29 October 2024. The consultation closed on 10 December 2024 – all feedback can be accessed here

- DA: Delegated Act on Data Access – clarifies the procedures for researchers to access non-public data from VLOPs and VLOSEs under the DSA. It was adopted bv the European Commission on July 2, 2025 and came into force in Q4 2025.

- GDPR: General Data Protection Regulation, EU law regulating the processing of personal information

- EC: European Commission, as the the primary executive arm of the EU proposes laws and makes sure EU laws are properly applied. Under the DSA, the Commission has investigative and sanctioning powers regarding VLOPs and VLOSEs.

- VLOP: Very large online platform, with more than 45 million users in the EU per month, which has to abide by special rules under the DSA, including the data access provisions.

- VLOSE: Very large online search engine, with more than 45 million users in the EU per month, which has to abide by special rules under the DSA, including the data access provisions. When speaking of platforms here, it mostly means VLOPs and VLOSEs.

- DSC: Digital Services Coordinator, a new regulator each EU member state has to designate that has a big role to play in enforcing the DSA, particularly regarding data access for researchers

- DSC-E: Digital Services Coordinator of Establishment, DSC of the member state in which the intermediary service or its legal representative is established.

- API: Application Programming Interface, a set of rules, protocols, and tools that allows different software applications to communicate with each other. In the case of research data access, APIs can be used to programmatically request data from platforms without having to use a User Interface.

EU legal texts, such as regulations and directives, follow a standardised structure that includes:

- Title & Introductory Information

- Preamble with Recitals (Rec.) – Explaining the purpose and objectives of the act. Recitals are not legally binding but guide interpretation.

- Articles (Art.) – The core legal provisions, organised in numbered sections. Articles establish rights, obligations, procedures, and enforcement mechanisms.

- Annexes – Contain supplementary details, such as technical specifications, definitions, or procedural guidelines, which support the main articles.

ℹ️ How to read EU legislation? by Jasper Krommendijk & Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius (Blog: EU law analysis)

In this Q&A…

…the EU flag label 🇪🇺 denotes official communication from the EC.

…the document label 📄 indicates links to a legal text.

…the information label ℹ️ offers more in-depth reading.

…the yellow circle label 🟡 indicates that this link leads to another part of the Q&A.

…the construction sign 🚧 indicates information may change in the future.

…the warning sign ⚠️ indicates potential hurdles to data access.

…the handshake 🫱🏻🫲🏽 indicates an option to become part of the Interdisciplinary Network of Researchers around the DSA 40 Collaboratory.

Key information for DSA-based data access applications is boxed.

Researchers play a key role in the governance process envisioned by the EU’s Digital Services Act. Based on Art. 40 DSA, they have the right to be granted access to platform data to produce insights that help further our understanding of digital platforms as well as strong and sensible enforcement of new EU regulation.

This Q&A aims to equip researchers with the informational resources to understand

- the regulatory background of research access

- how researcher data access to (a) publicly accessible and (b) non-public data works and what issues exist

- what researchers can do to help make data access work the way it should

- what other data access options exist apart from data access for researchers

Overview DSA

What is the DSA?

The 📄 Digital Services Act (DSA) is a European Union regulation that creates standardised liability and safety rules with the goals of

- preventing societal risks like the erosion of election interference, the spread of illegal content

- protecting European platform users, in particular with regards to their fundamental rights

The DSA applies to a range of intermediaries, e.g., to online marketplaces, social networks, content-sharing platforms, app stores, and online accommodation platforms. (for more detailed information, see → 🟡 Who does the DSA apply to?)

To achieve its goals, the DSA prescribes, among other things, reporting of illegal activities, simplified terms and conditions, stronger protections for people targeted by online harassment, easy-to-use complaint mechanisms, bans on certain types of targeted advertising, and various transparency measures – like research data access.

As regulation, the DSA applies automatically and uniformly to all EU countries, without needing to be transposed into national law. Together with the Digital Market Act (DMA), it aims to provide a single set of rules across the whole EU to protect fundamental rights and create a level playing field for businesses.

ℹ️ Analysis of various aspects of the DSA, edited by Joris van Hoboken et al. (Verfassungsblog ebook, 2023)

ℹ️ Further information about the DSA by the EC

ℹ️ Digital Services Act: Article-by-Article Commentary, edited by Franz Hofmann and Benjamin Raue

ℹ️ Overall DSA timeline with deadlines for reports and evaluations

Why should researchers care about the DSA?

In order to properly understand and thus best regulate online platforms, EU regulators need expertise from academic and civil society researchers. Research thus is a foundation for strong and sensible enforcement of new EU rules for platforms.

However, in the past researchers faced obstacles when researching online platforms (cooperations failed, researchers reportedly have been pressured, data access tools have been closed or limited, and running experiments were likely tempered with) and even if industry-academia collaborations work very well, questions around researcher independence come into play.

Against this backdrop, European policymakers – pushed by academia and civil society – included a data access provision for researchers in DSA: 🇪🇺 Article 40 provides an unprecedented opportunity for researchers to better understand platforms and, ultimately, help independent regulators oversee platforms based on scientific evidence.

Yet, the implementation and enforcement of this data access framework remains a difficult and ongoing challenge. That’s why further collaboration, both within the research community and with policy makers, is important.

ℹ️ Impediments to privacy research and how the DSA might help by Konrad Kollnig and Nigel Shadbolt (Technology and Regulation, October 2023)

Aren’t there already data access rules in the EU?

No, there are no mandates for platforms to share data with researchers. The DSA is the first piece of EU legislation to include a legally binding data access regime for online platforms. This makes current efforts to get enforcement right all the more vital.

So far, two of the major avenues for researchers to get platform data had been voluntary and flawed:

Voluntary measures by individual platforms

Some platforms offer APIs or other one-off voluntary cooperations with researchers. These measures have overall not been successful: They are rare and carry the risk that platform providers may influence the study design or data itself and thus also the results.

ℹ️ The state of social media research APIs & tools in the Digital Service Act era by Fabio Giglietto & Massimo Terenzi (2024)

ℹ️ Social media algorithms can curb misinformation, but do they? by Chhandak Bagchi et al. (2024)

ℹ️ Meta is getting rid of CrowdTangle — and its replacement isn’t as transparent or accessible by Sarah Grevy Gotfredsen & Kaitlyn Dowling (2024)

Codes of Practice on Disinformation: Multi-platform pledge to cooperate with researchers on disinformation:

The voluntary “Code of Practice on Disinformation”, a multi-platform pledge to cooperate with researchers on disinformation led by the EC, that tries to get platforms and other stakeholders to commit to tackling issues stemming from the spread of disinformation. Big tech companies like Instagram and TikTok have signed up to (parts of) this voluntary code. One pillar is called “Empowering the Research Community”, which includes commitments to provide automated access to public data and to support the research community.

ℹ️ Background on the Code of Practice on Disinformation by the EC (press release, June 2022)

While a step in the right direction, the benefits for researchers have limits: Most importantly, the pledge is voluntary. There are evaluation indicators for each commitment and measure, but fundamentally, platforms are free to join and leave the Code as they please (for instance, Twitter is said to have left the Code in May 2023). Even if they nominally adhere to the Code, platforms’ efforts to “empower the research community” have been underwhelming, as this analysis shows:

ℹ️ Transparency Center with report archive

In addition, the Code only covers research on disinformation. This is certainly a big field but the DSA’s scope covering systemic risks (explained 🟡 here) is much wider.

Who does the DSA apply to?

ℹ️ Which providers are covered? by the EC

The DSA applies to organisations that provide online intermediary services in the EU. This includes ‘mere conduit’ servicesA service that provides access to a communication network or transmits information provided by a service recipient.

Examples: broadband providers, mobile network operators, internet service providers, internet exchange points, direct messaging services (not IM services), VOIP, VPNs, Wifi/WLAN, DNS, TLD registries, domain registrars, digital certificate issuers., ‘caching’ servicesA service that transmits information provided by a service recipient in a communication network, involving the automatic, intermediate and temporary storage of that information, performed for the sole purpose of making onward transmission more efficient to other recipients upon their request.

Examples: Content Delivery Network (CDN), proxy server, web caching., and hosting servicesA service that consists of the storage of information provided by, and at the request of, a recipient of the service.

Examples: online marketplaces, app stores, social media platforms, collaborative economy platforms, cloud services, Iaas (servers, networking), PaaS (H/W, stack, infra, dev tools), SaaS (cloud apps/services), serverless computing, file transfer services, file storage services. – organisations that at the request of recipients of a service, provide storage, transmission, and/or disclosure to third parties of information online – as well as online platforms that store and disseminate information to the public.

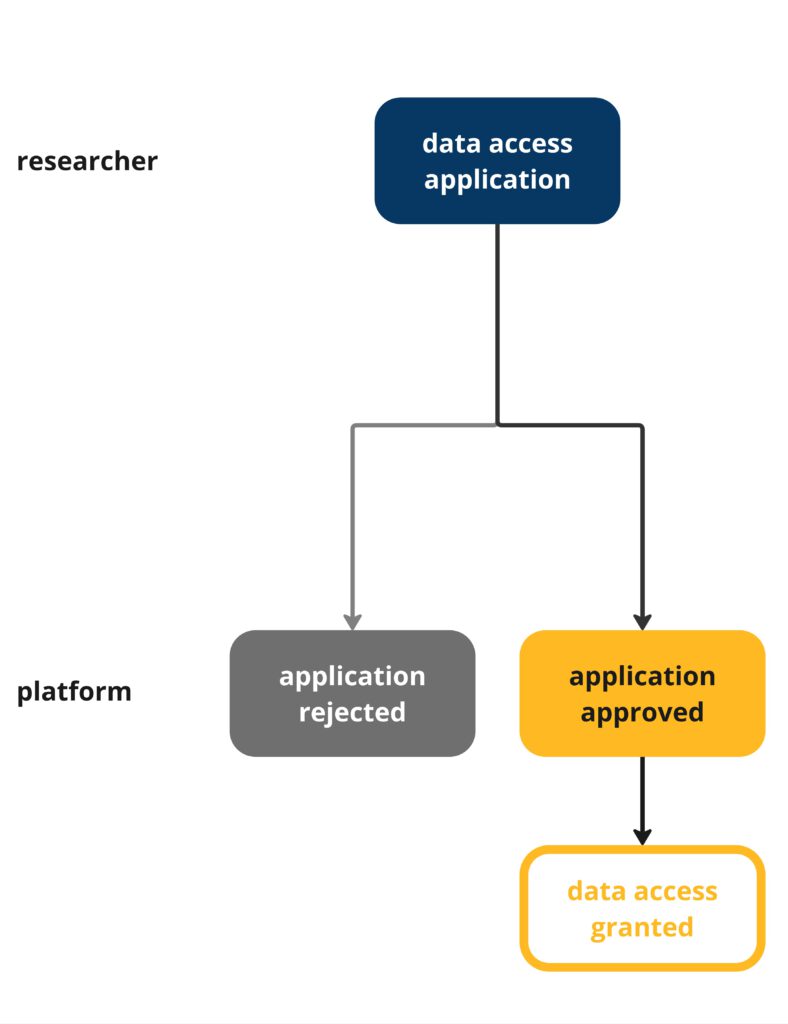

In terms of obligations that apply to the service provider, the DSA distinguishes between different categories.The DSA is considered an asymmetric regulation. This means that the strictest obligations, including data access requirements, are only imposed on the biggest and most-used players: VLOPs and VLOSEs, which are online platforms with 45 million or more average monthly active recipients of the service in the EU (representing 10% of the population of the EU).

Platforms have to report their user numbers to the regulators and the Commission ultimately designates the VLOPs. VLOPs generally have to report on 🟡 systemic risks on their services and have to mitigate them.

📄 VLOP definition and designation process: Article 33 DSA

🇪🇺 Overview of VLOPs by the EC (continuously updated)

ℹ️ Context and analysis by Martin Husovec (journal article, February 2023)

ℹ️ Who does it apply to? by the Irish DSC Coimisiún na Meán

What is a Digital Services Coordinator?

The Digital Services Coordinator (DSC) is an oversight body that the DSA requires each EU member state to set up or appoint. In the data access context, they are the single-most important body that researchers will interact with. Member states had until February, 2024 to nominate their DSCs. The vast majority of countries house the DSC at an existing agency such as their telecommunications, consumer protection or media regulator.

Each DSC coordinates various agencies at the domestic level, collaborates with other DSCs and the EC at the EU level and enforces the DSA regarding all “not very large” platforms in their respective country. As such, they play an important ‘coordinating’ – but also an important regulatory role: The DSCs themselves can request data from VLOPs, and are the ones “vetting” 🟡 non-public data access requests from researchers.

As the DSCs are such an important point of exchange, the DSA requires them to:

- be completely independent from commercial and governmental influence

- to have sufficient resources

- be impartial and transparent

🚧

Not all EU member states have their DSCs in place. Therefore the EC has opened 🇪🇺 infringement procedures against several member states. Recently, the EC:

referred Poland to the Court of Justice of the EU for failing to appoint and empower a DSC and to establish rules on penalties for infringements.

referred Czechia, Cyprus, Portugal and Spain to the Court of Justice of the EU for failing to empower their designated DSCs and for not setting out the rules on the penalties.

raised a reasoned opinion against Bulgaria for failing to empower a national DSC and for not setting out the rules on the penalties.

Isn't the Irish DSC a bottleneck for researchers?

Potentially. Most requests will likely be decided by the Irish DSC because those platforms that have so far been of highest interest to researchers are based in Ireland: e.g. Meta’s VLOPs, YouTube, TikTok and X.

The Irish DSC has publicly signaled that they are well aware of their crucial role for data access. Ireland was one of first countries to officially designate their DSC, housing it at the new Coimisiún na Meán (Media Commission). There are promising signs that Ireland will not be a bottleneck but in practice it remains to be seen whether these efforts will work. The Media Commission has only been around since March 2023 and is in the process of building capacities. Depending on the scale of researcher requests, there is a risk the Irish DSC could be overwhelmed.

Other risks refer not only to the Irish DSC, but all of them. For instance, if researchers apply in their countries of residence first, a well-done initial opinion by the national DSC can greatly aid the Irish colleagues. That means that DSCs need enough staff, resources and expertise as well as a fitting organisational structure to handle the vetting process. Without a deep understanding of systemic risks and tried networks to academia and civil society, DSCs will be at a loss to support EU platform research.

ℹ️ Overview of DSCs’ responsibilities and ideas for strong DSCs by Julian Jaursch (Verfassungsblog post, October 2022)

ℹ️ Analysis on why DSCs need strong data and research units by Julian Jaursch (DSA Observatory blog post, March 2023)

ℹ️ Overview of all DSCs across Europe by Julian Jaursch (SNV, February 2024)

Map of EU member states and their designated DSCs (yellow).

Hovering over countries shows which VLOPs/VLOSEs have established their main establishment or legal representative there.

Table with states of establishment only

| Member State | DSC | Responsible for | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 🇮🇪 | Ireland | Comisiún na Meán (Media Commission) | Alphabet (Google Maps, Google Play, Google Search, Google Shopping, YouTube), Apple (AppStore), ByteDance (TikTok), Meta (Facebook, Instagram), Microsoft (Bing, LinkedIn), Pinterest (Pinterest), X (X), PDD Holdings (Temu), Roadget Business Pte Ltd (Shein) |

| 🇳🇱 | Netherlands | Autoriteit Consument & Markt (Authority for Consumers and Markets) | Alibaba (Aliexpress), Booking (Booking.com), Snap (Snapchat) |

| 🇨🇾 | Cyprus | Αρχή Ραδιοτηλεόρασης Κύπρου (Cyprus Radiotelevision Authority) | Aylo (Pornhub) |

| 🇩🇪 | Germany | Bundesnetzagentur (Federal Network Agency) | Zalando (Zalando) |

| 🇨🇿 | Czechia | Český telekomunikační úřad (Czech Telecommunication Office) | WebGroup Czech Republic (XVideos) |

| 🇱🇺 | Luxembourg | Autorité de la concurrence (Competition Authority) | Amazon (Amazon Marketplace) |

🇪🇺 List of the DSCs by the European Commission

📄 Rules on the DSCs: Articles 49 to 51 DSA

ℹ️ Overview of DSCs’ responsibilities and ideas for strong DSCs by Julian Jaursch (Verfassungsblog post, October 2022

ℹ️ Overview of all enforcement authorities and the cases they have taken against online platforms by EDRi

What other rules in the DSA might be useful for researchers?

While Article 40 enables access to public and non-public data, the DSA also includes further transparency measures that can be used to gain insight into online platforms. Leerssen (2024) distinguishes traditional, static measures of algorithmic transparency and more systemic and dynamic disclosure rules that should enable platform observability:

| Algorithmic transparency | Platform observability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Public mechanisms | Access for researchers | ||

| Content curation | Explanations for the “main parameters” of recommender system algorithms (Art 27) | Public content APIs & scraping (Art 40(12)) | Access rights for vetted researchers (Art 40(4)) |

| Ad targeting | Explanations for the “main parameters” of ad targeting decisions | Ad archives (Art 39) | |

| Content moderation | Explanations for content moderation policies and decisions (Art 14, 17) |

Statement of Reasons database (Art 24(5)) |

|

| Aggregate reporting on content moderation (Art 15, 24, 42) |

|||

ℹ️ Outside the Black Box: From Algorithmic Transparency to Platform Observability in the Digital Services Act by Paddy Leerssen (May 2024) – Table (p. 19)

ℹ️ What can the Digital Services Act do for you? Tips for navigating platform [in]transparency by John Albert (February 2025)

Online advertising databases

⚠️

The DSA calls on VLOPs to create ‘ad repositories’, collecting all online advertising along with some metadata, such as their source of funding or display period. This ad archive is meant to encourage scrutiny not only by consumers and journalists, but also by researchers studying paid communications online.

📄 Rules on online ad repository: Article 39 DSA

ℹ️ Full Disclosure: Stress testing tech platforms’ ad repositories by Mozilla (2024)

ℹ️ On key traits that make for an effective ad archive API by Mozilla and independent researchers

Content moderation decisions database

⚠️

Due to the technical and hardware requirements for the tooling, the Transparency Database is currently only fully accessible to researchers with technical skill and infrastructure.

Platforms need to provide information on content removal decisions that the EC will put in a machine-readable database. The Commission set up a transparency database that is constantly being populated with ‘statements of reasons’ for why content has been blocked or removed.

This could be useful for researchers interested in how content moderation on platforms works, how companies report to users and authorities, and what scale their content moderation efforts have. The EC provides a Dashboard with aggregate information, a Research API for all statements submitted within the last six months. More elaborate insights can be gained through additional tools developed by the EC.

📄 Rules for the transparency database: Article 24(5) DSA

🇪🇺 Commission’s DSA Transparency Database

ℹ️ Big data, small answers: How the DSA Transparency Database falls short of its regulatory objectives by Groesch et al. (2025)

Digital Services Terms and Conditions Database

⚠️

Since the database is accessible as a git repository, the Digital Services Terms and Conditions Database is currently only fully accessible to researchers with some technical skill and knowledge of git.

Platforms are required to offer easy-to-understand terms and conditions. The Digital Services Terms and Conditions Database lists platform contracts. Researchers could, for example, use this to understand how and when platforms change their terms and conditions. The database is maintained by verified users and automated systems based on open source software developed by Open Terms Archive.

📄 Rules on terms and conditions: Article 14 DSA

🇪🇺 Commission’s Platforms Contracts Database

Platform Reports

An overview of what reports, guidelines and databases are mentioned in the DSA can be found in this spreadsheet.

Transparency Reports

🚧

In November 2024, the Commission established 🇪🇺 harmonised templates and reporting periods to ensure consistency within and between its transparency tools. The first harmonised reports are expected in early 2026.

Providers of intermediary services have to publish aggregated reports on their content moderation, VLOPs and VLOSEs every six months, and other services at least once a year.

📄 Rules on transparency reporting: Article 15 , Article 24, Article 42 DSA

🇪🇺 Overview of the published Transparency Reports

Risk Assessment and Audit Reports

VLOPs and VLOSEs have to report at least annually on the risks arising from their services and the mitigation measures taken. Additionally, they have to be subject to independent audits.

The audit reports must be made public no later than three months after receipt, together with the risk assessment reports, the risk mitigation measures implemented, a report on how they have implemented the recommendations received from their auditors, and information on any relevant consultations.

📄 Rules on risk assessment and audit reporting: Article 34, Article 35, Article 37 & Article 42(4) DSA

🇪🇺 Overview of the published Risk Assessment and Audit Reports

Research data access in the DSA

VLOPs & VLOSEs – Which platforms have to provide data?

⚠️

Smaller platforms are not covered under the DSA data access regime. The DSA does not require “non-VLOPs”, that is, services with less than 45 million recipients in the EU per month, to follow its data access rules. While those platforms could share data on their own terms, this would be on a voluntary basis. While this set up limits research possibilities, it is likely the result of the need to balance researcher access with high burdens for smaller platforms (although small and micro enterprises are exempt from many DSA rules altogether).

Only VLOPs and VLOSEs are covered by the data access rules. These are platforms which distribute content to at least 45 million monthly users in the EU.

As the 🟡 VLOP overview shows, the 🟡 Irish DSC will play an especially important role for data access matters because many platforms of high interest to researchers have the EU headquarters there. That’s why DSCs, and particularly the Irish one, need to have strong capabilities to vet researchers and understand systemic risks.

🚧

Cross-platform research is possible but complex. Data access to multiple VLOPs can be requested to study cross-platform systemic risks but this currently requires individual applications to the relevant platforms.

What kinds of access are there?

🚧

While the DSA has been a fully applicable law since February 2024, the non-public data access regime is not fully functional yet. The European Commission specifies it in the Delegated Act (DA), published on July 2, 2025. Researchers can apply for access to non-publicly available data when the DA enters into force, which is expected for Q4 2025.

The DA is based on an initial consultation the EC held in May 2023 (🇪🇺 all responses), and feedback to a draft text published in October 2024 (🇪🇺 all responses).

⚠️

The access measures in place to address researchers’ use of publicly accessible data are not yet optimal and have faced 🇪🇺 scrutiny by the EC. It has:

- sent several requests for information to VLOPs to figure out how they follow the rules

- opened formal proceedings against AliExpress, Meta, Tiktok which include suspected shortcomings in giving researchers access to publicly accessible data

- released preliminary findings in proceedings against X which includes findings that X fails to provide access to its public data to researchers

Data access is only open to researchers that can show show that their research solely furthers the understanding or mitigation of 🟡systemic risks in the EU. Notably, data access is conditioned on the purpose of access and not the origin of researchers.

This means that researchers from outside the EU can also use the DSA to request data from platforms – as long as they are researching systemic risk in the EU. Data access applications are submitted per research proposal. This means that theoretically multiple researchers from multiple institutions can apply for joint data access if they meet the vetting criteria. In case of research collaborations, we strongly recommend mentioning data sharing or joint processing in the application!

Article 40 of the DSA outlines two kinds of data access:

- Access to data publicly accessible in platforms’ online interfaces (also called “public data access”) in Art. 40(12)

- Privileged access to platform data (also called “non-public data access”) in Art. 40(4).

There are differences with regard to who can request access, to whom the request must be made, and which obligations come with data access, depending on the kind of access requested.

| Art. 40(12) “public data access” | Art. 40(4) “privileged/non-public data access” | |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | According to DSA 📄 Article 40(12), researchers from research institutions and non-profit bodies, organisations and associations shall be granted easy and uncomplicated access to data that is publicly accessible in the VLOPs’ and VLOSEs’ online interfaces, provided that they fulfil the relevant conditions (📄 DSA Article 40(8)(b–e), further are explained 🟡 here). | According to DSA 📄 Article 40(4), access to VLOPs’ and VLOSEs’ data that may not be publicly accessible can only be requested by “vetted researchers“ who meet all requirements set out in DSA 📄 Article 40(8), which are explained 🟡 here. |

| Application | Researchers submit their application directly to the platform provider. | Researchers submit their data access application to the relevant DSC, which forwards valid requests to the providers. |

| Purpose of Access | Data access is granted solely to research which contributes to

| Data access is granted solely to research which contributes to

|

| Example Data Types | Based on 📄 DSA, Rec. 98:

| Based on 📄 DA, Rec. 13:

|

What data (formats) can researchers receive?

The DSA does not include a list of data formats that VLOPs have to work with. Instead, researchers have to specify what type of data they need to study systemic risks. Then, the DSA requires platforms to provide “appropriate interfaces specified in the request, including online databases or application programming interfaces” (📄 Article 40(7) DSA). This rather broad provision seems to cover various types of data and data formats.

The format therefore depends largely on the modalities of data access: while access via APIs most commonly supports JSON format, access via online dashboards may offer the option to download .csv files. For accessing non-public data, the DSC-E determines the access modalities (cf. 📄 DA, Art. 9)

See the sections on 🟡 public and 🟡 non-public data for more details.

ℹ️ A beginner’s guide to JSON, the data format for the internet by Sam Robbins (Stack Overflow/blog, June 2022)

What remedies are there if platforms don’t comply or act nefariously?

⚠️

It cannot be ruled out that data access requests might fail because of platforms’ refusals or inaction (such as delay tactics/question loops, pretended excuses, open refusal to share data, prevention of publicly available data scraping, provision of too much/useless/manipulated data, ensuing reputational damage). These risks can likely only be reduced by strong, independent regulators as well as a vocal and well-coordinated researcher community.

Still, there are some possible avenues for researchers and regulators to respond to non-compliance:

Complaints

⚠️

Currently no institution provides researcher-specific complaint forms and therefore has to be contacted through email or consumer-facing forms in the case of researcher complaints

Researchers can file complaints about potential DSA violations including supporting documentation (e. g. screenshots, exchanges with the platform, code output returned by an API, etc. …) with

- their national DSC or the DSC-E

- the EC’s Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CNECT)

📄 Rules for complaints: Articles 53 DSA

Fines and other penalties

The DSA foresees sanctions for a variety of violations, including breaches of data access rules. However, fines (up to 6 % of platforms’ total worldwide annual turnover) are one of the last resorts. Beforehand, the Commission must try to work out an “action plan” with VLOPs to stop non-compliance.

📄 Rules for fines and penalties: Articles 52 DSA

📄 Rules for non-compliance: Articles 73 to 75 DSA

Systemic Risks – For which topics can researchers request data access?

📄 Article 40 DSA recognises the following research purposes as sufficient for data access:

- conducting research that contributes to the detection, identification and understanding of systemic risks in the Union, as set out pursuant to 📄 Article 34(1) DSA [for access based on 40(4) and 40(12)]

- assessment of the adequacy, efficiency and impacts of the systemic risk mitigation measures pursuant to 📄 Article 35 [for 40(4) access exclusively]

All data access requests have to relate to what the DSA calls “systemic risks” in the EU as defined in Article 34(1) DSA, which provides a set of minimal examples of systemic risk categories which have to be taken into consideration by VLOPs in their risk assessments:

| Systemic Risk Categories | 🔍 Examples |

|---|---|

| (a) Dissemination of illegal content ⚠️ the DSA does not define what is “illegal” → illegal as defined by existing EU and national law | Studying the spread of posts inciting violence or containing libel ℹ️ in their Guidance for Trusted Flaggers the 🇮🇪 Irish DSC lists a minimum of 63 distinct categories of illegal content |

| (b) Negative effects for the exercise of fundamental rights enshrined in the 📄 Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (esp. to human dignity, respect for private and family life, protection of personal data, freedom of expression and information, non-discrimination, respect for the rights of the child, a high-level of consumer protection) | Studying the uptake and consequences of privacy settings; studying biases in content moderation practices and their effects on representation/non-discrimination |

| (c) Negative effects on civic discourse, electoral processes and public security | Studying whether viewing more or less content from political parties affects the likelihood to vote; studying the spread of false information regarding an election date; studying algorithmic recommendations of extremist content |

| (d) Negative effects in relation to gender-based violence, the protection of public health, the protection of minors and relating to someone’s physical and mental well-being | Studying to what extent exposure to certain types of content affect individuals or groups at risk of depression |

The systemic risk categories provided in Art. 34(1) DSA are defined in relatively broad terms, non-exclusive (meaning they can overlap) and non-exhaustive (meaning that they do not claim to cover all potential systemic risks that can occur).

Thus, a lot of research questions can potentially relate to one or more of the given systemic risk categories. Researchers should try to clearly demonstrate

- how their research is related to systemic risk (optimally, but not limited to, the minimal examples detailed above)

- (and | or) how their research assesses risk mitigation measures

Accessing publicly available data

"Providers of very large online platforms or of very large online search engines shall give access without undue delay to data, including, where technically possible, to real-time data, provided that the data is publicly accessible in their online interface by researchers, including those affiliated to not for profit bodies, organisations and associations, who comply with the conditions set out in paragraph 8, points (b), (c), (d) and (e), and who use the data solely for performing research that contributes to the detection, identification and understanding of systemic risks in the Union pursuant to Article 34(1)."

📄 Article 40(12) DSA

Who can access publicly available data?

The legislator has defined researchers for this kind of data access relatively broadly. Since all “researchers, including those affiliated to not for profit bodies, organisations and associations” who meet the above requirements are eligible for data access no affiliation to an academic research institution is necessary. 📄 Art. 40(12) DSA therefore creates an opportunity for civil society organisations or journalists. The 🟡 platforms’ application forms will ask applicants to demonstrate that they meet the specific requirements.

The DSA obliges platforms to provide access to publicly available data for researchers who fulfil the relevant conditions, set out in 📄 Article 40(8b-e) DSA:

(b) they have to be independent from commercial interests;

(c) their application has to disclose the funding of the research;

(d) they have to be capable to fulfill the specific data security and confidentiality requirements corresponding to each request and to protect personal data, and describe in their request the appropriate technical and organisational measures that they have put in place to this end;

⚠️

This condition means that researchers have to ensure data security and data protection measures. If you plan to request data access, make sure to check if there is existing data protection and security infrastructure at your institution.

ℹ️ some keywords: Access Control, Anonymisation, Data Minimisation, Storage Duration & Location and Purpose Limitation

(e) their application has to demonstrate that their access to the data and the time frames requested are necessary for, and proportionate to, the purposes of their research, and that the expected results of that research will contribute to the purposes laid down in paragraph 4

⚠️

This condition requires researchers to justify the data access they are applying for through the purposes of their research. Applications should therefore clearly state the reasoning for the requested data access.

What does publicly accessible data mean?

Data that can be accessed based on 📄 Article 40(12) DSA must be “publicly accessible in [the platform’s] online interface”. The DSA itself does not define clearly what types of data can be requested.

📄 Rec. 98 DSA provides some examples for the kinds of data included in this definition, such as “aggregated interactions with content from public pages, public groups, or public figures, including impression and engagement data” (e.g. number of reactions, shares, comments).

🚧

“Publicly accessible data” is a very broad concept, without clearly defined, agreed-upon bounds and thus could also include other data points, such as highly disseminated data or data describing the user interface or platform design. What data points will eventually be considered publicly available, is dependent on requests made by researchers.

ℹ️ Overview of data types available through select platforms’ existing access modalities by Democracy Reporting International (2024)

All 🟡 platform application forms require researchers to specify the types of data requested for their systemic risk research. For their data access application, researchers should thus have a rough idea of what kind of publically available data they need.

How does the access process work?

How to request publicly available data?

For getting public data, researchers send their request to the relevant platform for vetting.

⚠️

Most VLOPs/VLOSEs have published specific application forms for data requests under the DSA. While essentially based on Article 40(12) DSA, the information requested by the platforms is varied in structure and level of detail. In some cases, more information is requested than is necessary.

| AliExpress | Dataworks API and datasets, documentation very limited | Pornhub | |

| → Application form | → Info → Email: dsa@pornhub.com |

||

| Amazon | No formal program, allows non-commercial scraping | Shein | |

| → Application form | |||

| Apple App Store | No formal program | Snap | Contact point, format csv.file |

| → Info → Email: dsacompliance@apple.com |

→ Info → Email: DSA-Researcher-Access@snapchat.com |

||

| Bing | API, Webmaster Tools, datasets covering misinformation & social trends | ||

| → Info → Application form |

|||

| Booking.com | Researchers Data Request Portal, format unclear, likely allows scraping | Temu | |

| → Info → Application form |

→ Info → Application form |

||

| Google Researcher Program | TikTok | Research API, requires registration | |

| → Info → Application form |

→ Info → Codebook (Documentation) → Application form |

||

| Google Maps API, Google Cloud Console dashboard, Google Request Records for limited scraping |

Wikipedia | Outstanding research access: APIs, scraping, downloadable datasets, built-in exploratory tools | |

| → Info | → Info → Wikimedia downloads → API Parsed infobox |

||

| Google Play Developer API, Console, permission for limited scraping |

X | tiered API access, comprehensive documentation | |

| Google Search Search Researcher, Result API (SRR API), permission for limited scraping |

→ Info, Developer terms: non-commercial use → Application form |

||

| Google Shopping Content API for Shopping, Merchant Center dashboard, permission for limited scraping |

XNXX | ⚠️ minimal transparency | |

| API, scraping discouraged | XVideos | ||

| → Info → Terms Research Program → Application form |

→ Application form | ||

| Meta platforms (Instagram, Facebook) | API, no-coding interface, Meta Content Library | YouTube | Research Program, Data API v3, excellent documentation, scraping possible |

| → Info → Application form (requires registration) |

→ Info → API Documentation/ Codebook → Application form |

||

| Research program, format unclear | Zalando | ⚠️ minimal transparency: no dedicated research portal, only DSA Single Point of Contact | |

| → Info → Application form |

ℹ️ The state of social media research APIs & tools in the Digital Service Act era by Fabio Giglietto & Massimo Terenzi (2024)

🚧

We are developing a tool to simplify the application process for public access to data. Stay tuned by 🫱🏻🫲🏽 subscribing to our newsletter.

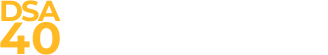

The VLOPs/VLOSEs then check whether the application is justified. Ideally, they quickly decide to

a) either reject the request

b) or to approve the request and give the researcher access to the appropriate access modalities.

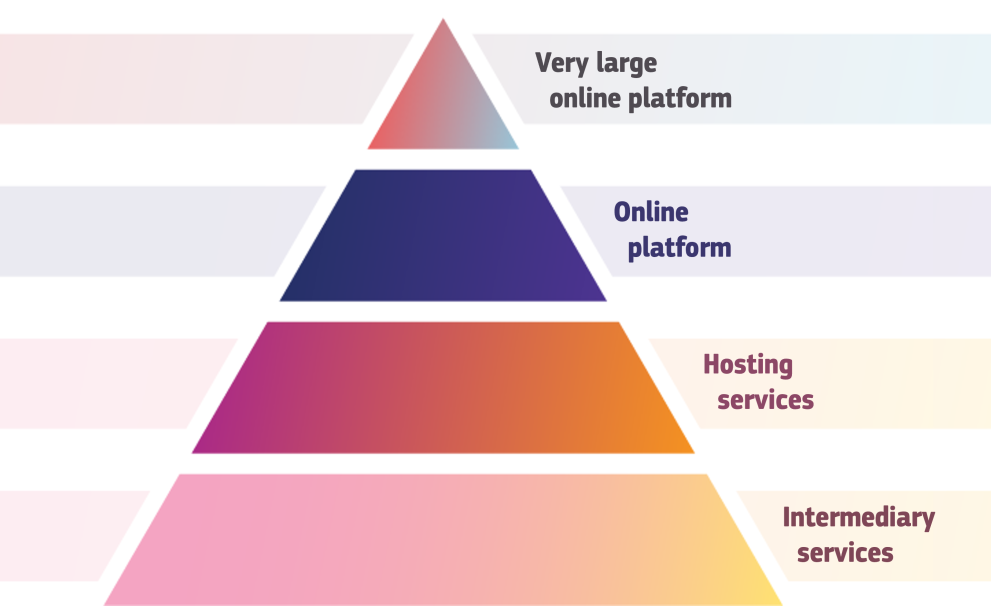

| Ideal process for requesting publicly available data | Empirical process for requesting publicly available data |

|---|---|

|  |

⚠️

Currently, the ideal process for access to publicly available data is likely to be more complicated for you, as platforms might take some time to reply and might also request more information for the vetting of your access application. Therefore, the process we see based on the applications submitted to our 🫱🏻🫲🏽 DSA Data Access Tracker, most of the time includes a feedback loop which may further extend the time until a decision on the application is reached.

How long does it take?

While 📄 Art. 40(12) DSA contains the wording that access should be granted “without undue delay”, it doesn’t clarify exactly how quick the platform providers have to process access requests.

⚠️

Insights from our 🫱🏻🫲🏽 DSA Data Access Tracker show for 11 TikTok und 16 X applications that on average these platforms take between 1 and 2 months respectively to decide on an access applications submitted by researchers. However, some X applications also show processing times above 200 days.

What about scraping?

Many researchers and ℹ️ civil society organisations have long called for legal clarity regarding scraping of social media sites and other platforms. While the DSA does not explicitly mention scraping, 🇪🇺 comments made by the EC as part of their proceedings against VLOPs indicate that scraping constitutes a permissible means of independent data access.

⚠️

Scraping should still be done responsibly, meaning researchers should still fulfill the vetting criteria referenced in 📄 Art. 40(12) DSA.

Accessing non-public data

"Upon a reasoned request from the Digital Services Coordinator of establishment, providers of very large online platforms or of very large online search engines shall, within a reasonable period, as specified in the request, provide access to data to vetted researchers who meet the requirements in paragraph 8 of this Article, for the sole purpose of conducting research that contributes to the detection, identification and understanding of systemic risks in the Union, as set out pursuant to Article 34(1), and to the assessment of the adequacy, efficiency and impacts of the risk mitigation measures pursuant to Article 35."

📄 Article 40(4) DSA

🚧

The EC provides details of this more advanced type of data access in its DA. We have updated this section accordingly. Access to non-public platform data will only be possible once the DA comes into force, which is due to happen in Q4 of 2025.

Who can access non-public data?

What are the conditions to become a vetted researcher?

In order to be granted ‘vetted status’, researchers must meet all the criteria set out in 📄 Article 40(8) DSA (see also Art. 9 DA).

(a) they are affiliated to a research organisation as defined in 📄 Art. 2(1) Directive (EU) 2019/790;

(b)–(e) same as 🟡 access to public data

(f) the planned research activities will be carried out for the 🟡 purposes laid down in paragraph 4;

(g) they have committed themselves to making their research results publicly available free of charge, within a reasonable period after the completion of the research, subject to the rights and interests of the recipients of the service concerned, in accordance with 📄 GDPR.

Contrary to access to public data, this kind of access also comes with a commitment to the open publication of the research results. However, as with access requests for public data, any data access request needs to be linked to the 🟡 systemic risks mentioned in the DSA.

Can non-academic researchers request data from platforms

Yes. The definition of “research institution” doesn’t only cover universities, but also other research-heavy organisations.

When defining research organisations, the DSA refers to 📄 Art. 2(1), of Directive (EU) 2019/790:

(1) ‘research organisation’ means a university, including its libraries, a research institute or any other entity, the primary goal of which is to conduct scientific research or to carry out educational activities involving also the conduct of scientific research:

(a) on a not-for-profit basis or by reinvesting all the profits in its scientific research; or

(b) pursuant to a public interest mission recognised by a Member State; in such a way that the access to the results generated by such scientific research cannot be enjoyed on a preferential basis by an undertaking that exercises a decisive influence upon such organisation

This definition potentially covers a wide range of non-university organisations and is therefore an opportunity for civil society organisations.

The DA provisions:

- Researchers can prove affiliation to a research organisation, e. g. with employment contracts or other legal associations (📄 Rec. 11).

- The requirements regarding independence from commercial interests could be met, e. g., by letters of commitment from the research organisation (📄 Rec. 11).

- To disclose funding, the application should include details of the contributions (funding entity, amount, type, duration, references to relevant EU projects, evaluations) (📄 Rec. 12).

Can researchers lose their 'vetted' status?

Yes.

If the DSC that granted the “vetted” status determines that the researchers don’t fulfill the vetting criteria anymore, it needs to inform the researchers of this finding their status will be terminated. Researchers can react to that finding before that.

Rules on losing the “vetted researcher” status: 📄 Article 40(10) DSA

Is the request per researcher or per research proposal?

According to the DA, the request is per research proposal. It could include several researchers, all of whom would have to prove their affiliation to the research organisation (cf.📄 Rec. 11).

Can research teams/consortia apply? Is data sharing among researchers allowed?

Yes, research teams can turn in joint data access requests. 📄 Article 2(3–4) DA distinguishes between:

- an ‘applicant researcher’, who requests access to data either individually, in a group or as part of an institution, and

- the ‘principal researcher’, who takes responsibility for the completeness and accuracy of the request and acts as the point of contact.

⚠️

Access to non-public data is subject to strict conditions, so that cooperation seems to be possible only with organisations that themselves meet all the vetting criteria laid out in 📄 Article 40(8) DSA.

Sharing data with other researchers seems possible, but should already be mentioned in the application!

What data can be accessed?

The regulator provides some examples for non-public data that could be requested in 📄Rec. 13 DA. Namely, the recital mentions data related to…

- information on users

- profile information,

- relationship networks,

- individual-level content exposure & engagement histories;

- interaction data

- comments or

- other engagements;

- content recommendations

- (e. g. used to personalise recommendations);

- ad targeting and profiling

- (e. g. cost per click data);

- testing of new features prior to their deployment

- (e. g. the results of A/B tests);

- content moderation and governance

- (e. g. on algorithmic or other content moderation systems and processes);,

- (e.g. changelogs, archives or repositories documenting moderated content, including accounts);

- prices, quantities and characteristics of goods or services provided or intermediated by the data provider

🚧

This list is neither final nor exhaustive and may vary over time. Researchers may freely ask for various kinds of data as long as their request is necessary for, and proportionate to the 🟡 purposes of their research. According to 📄 Art. 6 DA VLOPs and VLOSEs should also provide a ‘DSA data catalogue’ of their services, including both examples of available datasets and data structures available as well as indications on the suggested access modalities.

How does the access process work?

How to request data based on article 40(4) DSA?

📄 Art. 3 DA tasks the EC to set up and maintain the DSA data access portal, dedicated digital infrastructure to coordinate researchers, platforms, and DSCs. Researchers will be able to register and submit their access applications on this portal.

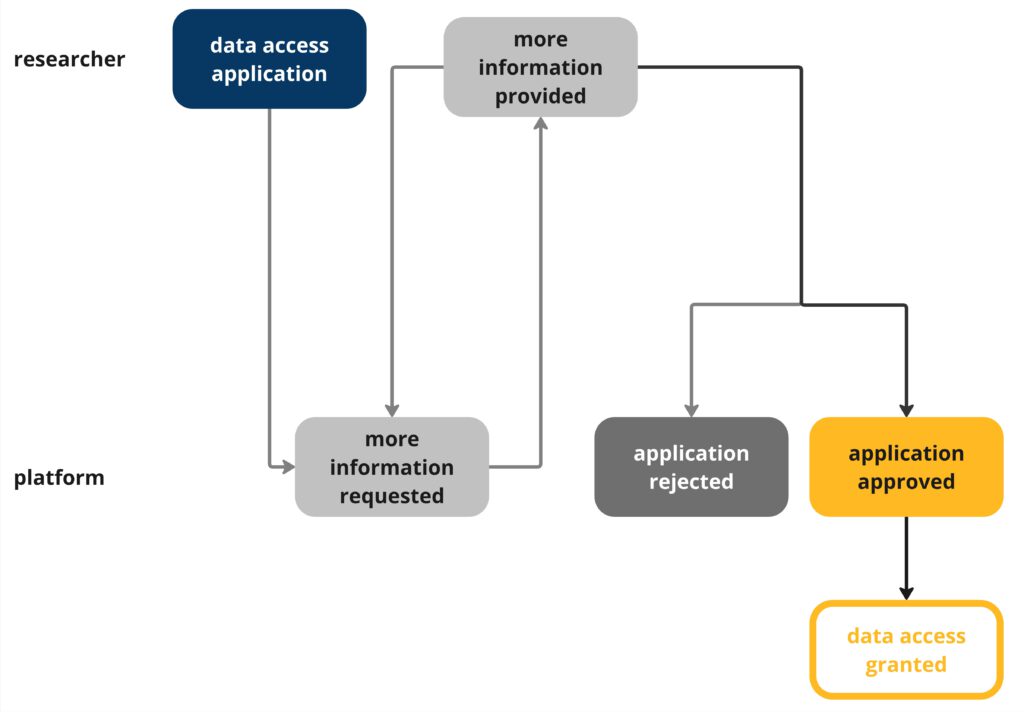

Here’s a simplified step-by-step guide on how the process works in case the application is successful:

- Researchers submit their data access application through the DSA data access portal and select a DSC to send it to. Two ways are possible:

- send it to the DSC where the platform is based (DSC of establishment), the direct way as this DSC has the final say

- send it to their national DSC (which forwards it to the DSC where the platform is based), which might take longer for researchers but could be beneficial since this takes pressure of the 🟡Irish DSC which will have a lot of requests to handle and would allow the national DSC to provide feedback to researchers and help them submit applications with a higher likelihood of acceptance by the DSC of establishment

- The DSC of establishment approves the access request within 80 working days

- Here’s where the DSC could reject a proposal

- If the data access application is approved, key information will be published in the data access portal so that other researchers can see what data can be accessed under which conditions

- Within 15 days after the DSC’s approval, the platform can ask for 🟡 amendments to the data access request

- Possible reasons include that the platform doesn’t have the data or that it sees security risks or risk for confidentiality, including 🟡 trade secrets

- The DSC of establishment will have to decide if the process for requesting amendment-request is justified

- The platform provides data access through the 🟡 specified modality to the researchers

| Max. duration | Time frame |

|---|---|

| 80 working days | for the DSCs–E to decide on the access request and formulate a reasoned request (📄 DA Art. 7) |

| 15 days | for the provider to formulate a request for amendment (📄 DSA Art. 5) |

| 15 days | for the DSC-E to decide on the request for amendment (📄 DSA Art. 6) |

| 5 working days | for the provider to request a mediation (📄 DA Art. 13(1)) |

| 20 working days | for the DSC-E and the provider to agree on and initiate the mediation (📄 DA Art. 13(4)) |

| 40 working days | for the mediation after its initiation (📄 DA Art. 13(9)) |

| ~ 175 working days | total |

📄 Article 40(13) DSA mentions the possibility of ‘independent advisory mechanisms’ which are specified in 📄 Art. 14 and Rec. 25, DA: Before formulating a reasoned request, or taking a decision on an amendment request, DSCs may consult experts. For example they could seek advice on determination of the access modalities, including appropriate interfaces.

- The experts should:

- be independent & impartial

- possess proven skills & have the capacity to perform the task without incurring undue delay

- To attest impartiality, the experts shall sign a declaration confirming that they

- (a) have no financial or personal ties to the data provider or the applicant researchers;

- (b) have no interest in the outcome of the data access process;

- (c) are free from any conflicts of interest.

- The DSC has to encode any of the consultations along with the received expert opinions in the portal AGORA

ℹ️ For a more detailed overview of the projected process of accessing non-public platform data, see Non-Public Data Access for Researchers: Challenges in the Draft Delegated Act of the Digital Services Act by LK Seiling, Ulrike Klinger, and Jakob Ohme (2024)

📄 Process for researcher data access: Article 40(4) to 40(11) DSA

What makes a ‘good’ data access application?

According to 📄 Art. 8 DA, to be complete, the data access application must include:

- Information on affiliation, independence from commercial interests and commitment to make results freely available, for each applicant researcher

- Information on funding

- Information about the data requested (format, scope, attributes, metadata, documentation)

- Explanation on the necessity and proportionality of the access/ why the project cannot be carried out with alternative means (like public data access)

- Information on proposed safeguards to mitigate possible risks in terms of confidentiality, data security and personal data protection

- Summary of the data access application (research topic, data provider, description of the data requested)

Three aspects seem particularly important to be considered by researchers:

- Clearly establishing that the research question is linked to 🟡 systemic risks

- Emphasising the necessity and proportionality of the access requests

- Ensuring proper safeguards against privacy and data security risk.

How to access the data?

📄 Article 40(7) DSA requires platforms to provide “appropriate interfaces specified in the request, including online databases or application programming interfaces”. This rather broad provision has been specified by the DDA, which names different classes of access modalities:

- secure processing environments

- data transfer

- “other access modalities to be set up or facilitated by the data provider”

🚧

Which other modalities are possible will become clear as researchers go through the access process and request different kinds of modalities.

Some VLOPs like Meta and TikTok already offer secure processing environments. However, secure research environments (like the National Safe Haven for Scottish health data) are also possible.

📄 Art. 15(2)–(4) DA asks platforms to:

- provide relevant documentation to the requested data, such as codebooks, changelogs and architectural documentation;

- not impose archiving, storage, refresh and deletion requirements that hinder the research referred to in the reasoned request in any way;

- not limit researchers’ use of analytical tools, including relevant software libraries unless otherwise specified

- not to impose any conditions to the processing of personal data other than those in the reasoned request

What could go wrong?

Isn’t the “trade secrets” exemption a huge loophole?

⚠️

According to 📄 Art. 40(5) and 40(6) DSA, platforms can ask for amendments to the data access requests if they have concerns about breaches of confidentiality, including trade secrets. This might entail a possible delay in the data access process that researchers should plan for.

However, even if platforms say that they can’t share certain data with researchers, platforms can’t ask to simply stop the data access request altogether. Instead, platforms can ask for amendments to the request and must make a suggestion for at least one alternative means to fulfill the request. So it could happen that researchers don’t get the data they asked for. Yet, alternative options must at least be discussed which could hopefully still allow them to carry out their research.

What options do platforms have to delay access?

The DA mentions the possibility for data providers to initiate mediation with the DSC-E if the DSC-E rejects their request for an amendment to a reasoned request for data. So far, the mediation procedure in Article 13 and Rec. 22 DA envisions a. o.:

- The data provider may initiate a mediation within 5 work days after receiving the DSCs decision on the amendment request.

- Participation is voluntary: The DSC-E is free to decide whether to participate and whether to invite the principal researcher.

- The platform provider and the DSC-E shall agree on a mediator that is impartial & independent, qualified and has relevant experience (with regards to the possible reasons for an amendment, laid down in 📄 Art. 40(5) DSA).

- The costs for a mediation shall be covered by the provider

- A mediation would not impact the rights of the parties to file juridical proceedings.

- The DSC-E may set a time limit for the mediation of max. 40 working days, beginning with its initiation.

- If no agreement is reached, the decision of the DSC-E on the amendment request remains valid.

- A summary record of the mediation shall be registered in AGORA through the DSC-E.

For details see: 📄 Article 13, Rec. 22, DA

If platforms invoke the 🟡 trade secrets exemption or provide other reasons for being unable to provide the requested data access, they may initiate amendments and mediation. Still, the DSA and the DA stipulate a clear 🟡 timeframe of 175 days for the access process. And even if mediation fails, the reasoned request remains valid. Thus, if the DSC-E publishes a reasoned request based on a researcher’s application, researchers will receive data and should be able to conduct their research. If platforms go beyond delaying the final decision on the delegated act by not providing data or not abiding by the reasoned request, researchers can still complain to the commission which may lead to fines and other penalties.

⚠️

The DA lacks information on options researchers can take if the data received does not conform to quality standards or does not allow for the research as intended.

Can researchers receive any resources for their applications or research from regulators?

⚠️

The DSA does not provide any explicit financial support by the regulators for data access.

Still, the DSA and the DA also do not mention fees or other costs for researchers. This creates an even ground for all researchers by not privileging researchers associated with well-resourced institutions. In all organisations, however, funding and resources will be a major determinant of whether researchers can actually make use of the data access provisions. This is one reason why coordination, support and infrastructure building around data access should be considered for further funding by the regulator in the future.

Currently there is no information on funding opportunities specific to data access. However, as the data access framework matures, specialised funding will likely become available. We will update this Q&A accordingly and update you in 🫱🏻🫲🏽 our newsletter in case relevant tenders or other relevant calls are published. 🚧 The resource question also pertains to DSCs: If they were well-staffed, have a dedicated scientific outreach unit and maybe even a budget to fund studies, this would be a positive development for researchers.

ℹ️ Analysis on why DSCs need strong data and research units by Julian Jaursch (DSA Observatory blog post, March 2023)

What now?

Immediate steps: Test the existing access regime

- Bookmark this page for quick access to all relevant research data access information

- 🫱🏻🫲🏽 Subscribe to our newsletter to stay up-to-date on matters of data access

- Check in with your institution to see: if they are planning to coordinate on data access requests and what resources they have available for you to draw on in your request

- Request data access, and if you do 🫱🏻🫲🏽 use our tracker to collect good and bad experiences so we can make the knowledge accessible to scientific and policy communities

Medium- and long term: Coordination and Relationship Building

Coordinate with other researchers from your university/research network to

- support 🟡 existing efforts

- build national/university/discipline-related coordination networks

- submit shared access requests

Build relationships with regulators to ensure a trusted exchange

- approach 🟡 your national DSC, esp. when preparing 🟡 40(4) access applications

- approach the EC in case of new policy developments or if you have information that might be relevant to 🟡 their investigations

Build relationships with platforms

- make use opportunities to get into contact with the platforms directly

- share your experiences 🫱🏻🫲🏽 with us and your research network

Who else is working on data access?

Initiatives analysing and tracking data access:

- Digital Democracy Monitor by Democracy Reporting International:

- Platforms Transparency Tools Tracker by Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics at the George Washington University: a helpful overview over Platform Access Mechanisms (not just VLOPs), Announcements, and Assessments of the various modalities

Exchange among researchers:

- Social Data Science Alliance

- Working Groups:

- Building Capacity for Data Access, Analysis, and Accountability

- The Gold Standard for Publicly Available Platform Data

Regulatory implementation and mixed stakeholder initiatives:

- Independent Intermediary Body to be set-up

Such an intermediary body could help DSCs with a peer-reviewed, independent vetting process and take some of the load off of the DSCs, which have other regulatory tasks to fulfill after all. It is unclear if/how the Commission will take up the suggestion for an intermediary body.

- Working Group 3 of the European Board for Digital Services

- Data Access Tracker by the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics

ℹ️ A mapping of DSA Article 40 Initiatives to foster data access to platforms by the Forum on Information & Democracy

ℹ️ Analysis and ideas on platform-to-researcher data access by a working group of the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO report, May 2022)

ℹ️ White paper calling for a CERN-like structure for studies on the information environment by Alicia Wanless and Jake Shapiro (2022)

Initiatives that generally work on the DSA:

Also a large number of civil society organisations are involved in producing guidance and analysis of the DSA and its article 40, as well as organizing workshops to coordinate actions. These include among others:

- Mozilla Foundation

- the Center for User Rights at the Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte,

- Algorithm Watch

- Democracy Reporting International

- Forum on Information and Democracy

- Center for Democracy and Technology

Please 🫱🏻🫲🏽 let us know about other DSA initiatives.

What are possibilities for data access apart from the DSA?

While not the focus of this project, there are a lot of other different methods to do research on platform data. See the ressources below, to get an overview.

ℹ️ Overview of other tools used for studying and monitoring social media by Chris Miles and Brandon Silverman

ℹ️ Toolkit for digital methods by the University of Helsinki

ℹ️ Digital data donations: A quest for best practices by Jakob Ohme and Theo Araujo