Newsletter

18.11.2024

# 2

#DSA40 Data Access Newsletter

Risk in focus: Election Interference

Hello everyone,

welcome to the second #DSA40 Collaboratory newsletter. Like last time, we’ll quickly update you on developments at the Collaboratory, summarise what happened in data access in the meantime, and take a look at (systemic) risk-related news, with a deep dive on a specific risk category.

A lot has happened since our last newsletter, which means we have a lot to get through. So let’s get to it.

Regarding the Collaboratory

We’re happy to announce that, with tracker insights, our website now also includes a more detailed summary of the responses to our data access tracker. Among other things, we provide an overview over the registered applications and their success, or the most popular risks studied. We will continuously update this overview and add more information and analysis. Click the link for more detailed information!

Data Access Update

It’s out! The Commission published the long-awaited draft of the delegated regulation on data access provided for in the DSA on 29 October. The act “specifies the procedures and technical conditions enabling the sharing of the data pursuant to Article 40, paragraph 4″, which means it is focused on non-public data. We will link our full response in the next newsletter, for now though, here’s our first short look at the draft delegated act (DDA):

What’s new?

For (vetted) researchers, the DDA clarifies (1) what information will be required for data access applications for non-public data (Art. 8), and (2) that groups of researchers, called “applicant researchers”, can apply for data access with one “principal researcher” as the main point of contact (Art. 2).

DSCs and providers of VLOPs/VLOSEs (or “data providers” in the DDA) also need to set up an easily accessible point of contact for the data access process (Art. 6). Additionally, data providers should provide an overview of the data inventory of their services, including “examples of available datasets” (Art. 6) and “indications on the data and data structures available” (Rec. 6), as well as a data access documentation (Art. 15), such as codebooks, changelogs and architectural documentation (Rec. 25). The DDA also provides a non-exhaustive list of current data that could be requested, such as data related to users, content recommendations, targeting and profiling, the testing of new features prior to their deployment, and content moderation and governance – while explicitly acknowledging that this might change over time (Rec. 12).

To facilitate this information exchange between stakeholders, the Commission will host a single digital point of exchange of information, termed “the DSA data access portal” (Art. 3-5), through which access requests (Art.8), reasoned requests (Art. 10), amendment requests (Art. 12), and requests for moderation (Art. 13) can be submitted. Also, it will provide public and non-public interfaces, containing information on the access processes registered on the portal.

What to watch?

Interestingly, the DDA mentions two categories of information to be published on the portal (Art. 11):

- a summary of the data access application submitted by the researchers

- the access modalities for the sharing of the data to the researchers

Art. 2(6) of the DDA defines access modalities as “legal, organisational and technical conditions determining access to the data requested”. So while the summary basically describes what data is shared by whom for which research project, the second specifies how the data is accessed.

Right now, the DDA specifies two modes of non-public data access (Art. 9/Rec. 16): one mode where the requested data is transferred to the researchers for further analysis, and one where researchers can access and analyse the data in secure processing environments. This means that as soon as data is transferred, researchers will have to ensure legal, technical and organisational measures to keep the data secure (Rec. 13). However, data of different sensitivity will require different safeguards which further complicates the determination of the appropriate modalities. Thus, if you plan to submit data access requests, we encourage you to either investigate the data security capacities in place at your lab or institution, or start to organise with other researchers to create shared services or infrastructures capable of ensuring secure data processing.

As always, we encourage you to take a closer look at the draft yourself. Also, if you would like to comment on the DDA, you can submit your feedback until 26 November to the European Commision. We will also formulate a response which we will share with you in one of the next newsletters. If you do not plan to submit a response but have a point you find crucial, you can send us your feedback to contact@dsa40collaboratory.eu and we will try to include it.

In case you want to gather a bit more information or join the ongoing discussion, we’d like to point you to the European Commission’s Info-Webinar for researchers (tommorrow, 19.11., 10-11:30am CET).

In other data access-related news, Ofcom, the UK’s media regulator, has opened a call for evidence regarding researcher data access for online safety-related research. They especially want to know about the extent to which independent researchers currently access information from providers of regulated services, challenges currently constraining information sharing; and how to improve access to relevant information. If you have experiences or opinions, make sure to let them know by 5pm on January 17th, 2025.

Last month also saw the fourth set of reports under the Code of Practice on Disinformation, in which the signatories – including Google, Meta, Microsoft, and TikTok – also detail how they enable researchers who want to study disinformation through the provision of data access. Here is a brief summary of the report:

| Bing | TikTok | |

|---|---|---|

Data applications in European Economic Area (EEA):

|

|

Data applications in the EEA Researchers API:

Commercial Content API:

|

|

|

|

| Meta | YouTube | Google Search |

|

Data applications (EEA)

|

[Fact Check Explorer Tool]

|

New features planned for MCL:

|

[Researchers API]

|

We see that platforms receive a varying amount of applications to their research data access programs. But we also see that some do not readily grant access. Researchers at University of Vienna had to learn this the hard way during the Austrian general election this September when several researchers were not granted access to the Meta Content Library. This restriction of access meant that researchers had to revert back to digital methods from the previous decade: studying political content on platforms based on screenshots.

But data access does not only cover the access process. Instead, being granted access is the prerequisite for all subsequent steps of sense-making. Naively, we would expect the data we receive through data access programs to be of high quality. However, since our last newsletter, it has become clear that data quality is a much more difficult topic than you would initially expect.

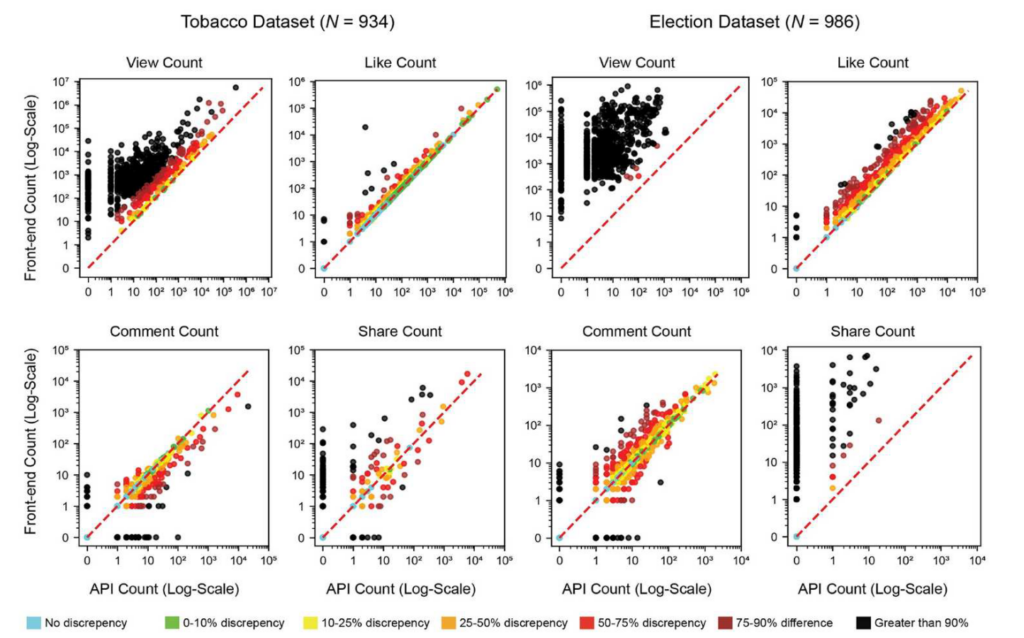

On Tech Policy Press Philipp Darius shared Lessons from TikTok’s API Issues During the 2024 European Elections. From April 2024 until shortly after the European elections, he and his collaborateurs had collected social media data on around 400 European parties. They came across substantial deviations between the views and shares returned by TikTok’s API and the data shown on their app or website. In their recent paper for Information, Communication & Society, Pearson et al. echo and expand these findings: they report that “metadata including views, likes, comments, and shares were frequently inaccurate by multiple orders of magnitude”, that data availability differed between the API and the user interface, and that API-based username filtering is buggy.

Figure from Pearson et al. (2024) showing the discrepancies for the different metadata (view, like, comment, share) for the two datasets under study (the data was re-collected from the API 19 and 10 days after original collection for the tobacco and election dataset respectively).

This highlights the importance of scraping as a quality assurance mechanism. It also emphasises the need for “periodic independent audits to verify the validity of research tools provided by tech companies” with functioning mechanisms to impose fines or sanctions if the maintenance of reliable data access infrastructure is neglected.

While TikTok has since adapted their API – accounting for the metadata metrics but not for the buggy search API – the situation is far from optimal: TikTok did not announce these API changes and also did not include reference to them in its changelog. This shows that apart from the technical aspects of data access the communication between platforms and researchers is also in dire need of improvement. This should not only include transparency about API changes and maintenance processes but also open public and accessible communication channels for the reporting of issues and bugs encountered by researchers. We hope that platforms proactively enable this constructive exchange and do not maintain this borderline-adversarial stance to researchers supporting their risk-mitigation efforts.

Darius and Pearson et al.’s research however was only possible because they had accessed public data which they could cross-reference with scraped data. But the delegated act in particular addresses the sharing of non-public data. Quality assurance for this kind of data is a lot more difficult, as a recent discussion in the eLetter section of the prestigious journal Science highlighted. But let’s start from the beginning…

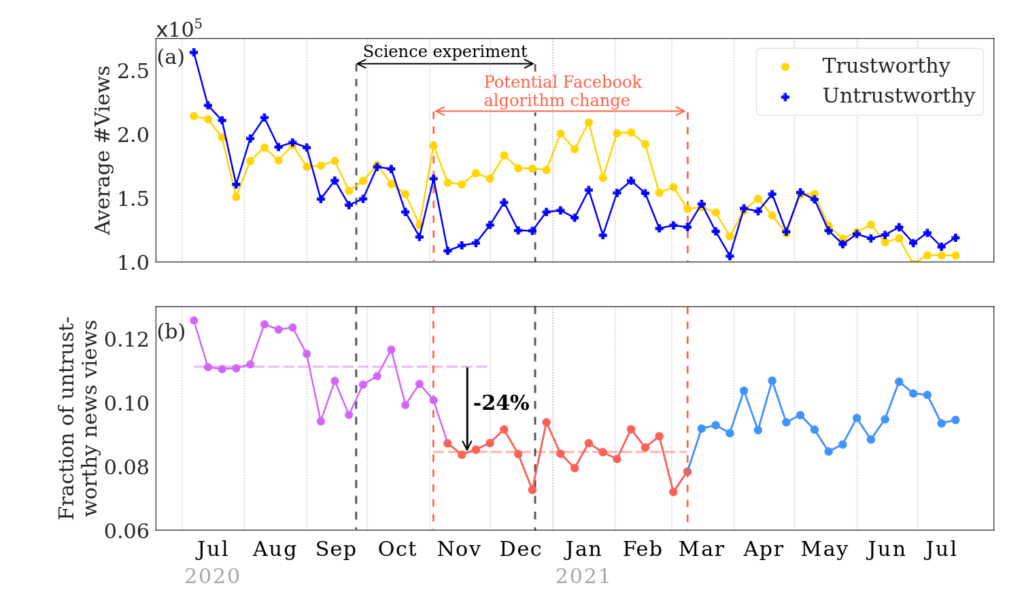

Last year, a high-profile, Meta-funded study by Guess et al. was published in Science which, one the basis of non-public data provided by Meta, claimed to find that Facebook’s algorithms successfully filtered out untrustworthy news surrounding the 2020 election and were not major drivers of misinformation. At the end of September 2024, Bagchi et al. drew the validity of the results into question. Using a different dataset provided by Meta (public data that has not been updated by Facebook since 2022!), they showed that Guess et al.’s study was conducted during a short period when Meta temporarily introduced 63 “break glass” changes to Facebook’s news feed. However, this change was not communicated in Guess et al.’s paper which strongly implies the researchers did not know about the manipulations.

Figure from Bagchi et al. (2024) showing the overlap between Guess et al.’s study period and the period of changes to Facebook’s algorithm.

Guess et al. have since responded questioning the claim of causality brought forth by Bagchi et al., but we still think that the fact that a platform could (and likely did) introduce changes to its algorithms during an ongoing study does not bode well for non-public data access in general.

Studies based on non-public data generally need to be pregregistred – this was the case for Guess et al., is required by Meta’s current access program, and, while not explicitly stated, to a limited extent is also part of the draft delegated act (Art. 10(d), Art. 8(9), Rec. 11) – which means platforms generally know ahead of time what researchers are looking for, giving them the chance to make changes to their algorithms or the data provided if they know they are being studied. This is a hard problem to tackle but an answer might be found in established scientific practice: When participants of a study anticipate its purpose and change their behaviour accordingly, this is usually referred to as demand characteristics. One measure to address these unwanted effects are single- or double-blind designs (in which either both the experimenters and the research subjects or just the subjects do not know if they are currently in the control or experimental condition). Therefore, some of the data quality issues related to non-public data access might be addressed by limiting the information disclosed to platforms while at the same time requiring platforms to provide public notifications in case of significant changes to their algorithms – after all the DSA regulates data access requests, not research requests.

Guess et al.’s study on the effect of platform algorithms during an election period actually provides a nice segway into this newsletter’s risk in focus…

Risk in focus:

Election interference

“If you are aware of any election integrity issues, please report them to the X Election Integrity Community”

– Elon Musk, CEO X.com, October 2024

What is electoral interference?

Election interference can broadly be described as attempts to manipulate the outcome of an election and covers a variety of different categories, like state and non-state interference in the electoral process or electoral fraud which includes the manipulation of votes, voter impersonation or vote buying. While relevant for any democracy, the topic has specific relevance in 2024, a year in which elections are held in at least 64 countries, representing about 49% of the world’s population.

How are online platforms and services related to this risk?

Typically, online platforms serve an instrumental purpose for actors trying to interfere in an election. To do so, such actors tend to leverage the platforms’ potential for content distribution to spread or amplify disinformation or to push content supporting their political agenda (acting on either the process or choice dimensions of the information space). The recent US election has seen multiple interference attempts like an AI-powered bot army on X spreading pro-Trump and pro-GOP propaganda, microtargeting of opposed messages to different voter groups, or foreign influence attempts to deepen existing divisions between citizens. However, a view that exclusively focuses on actors using platforms for their own ends, might neglect platform-related effects of algorithmic amplification or reward structures that might incentivise the spread of election-related disinformation. Taken together, both malicious actors and the platforms themselves, can thus contribute to a degradation of the information environment which in turn negatively affects citizens’ informed choice in an election.

What are possible risk mitigation measures?

In their role as mediators, platforms have the important role to check which kind of content is distributed widely. Thus, the most obvious risk mitigation measure platforms can choose is to take action against “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” and to delete, demote, or label harmful content. However, to determine harmful content requires a set of value judgements which some platforms have tried to avoid by suppressing political content altogether. The opposite approach would be to promote high-quality content (e.g. from trusted, authoritative sources or crowd-sourced quality assessment). Other options include changes to the user interface like contextual friction or changes to the recommendation algorithm that elevate content that resonates with diverse audiences. While fact checking is also often considered a potential mitigation measure, scientific studies have yet to establish a clear positive effect.

It is important to underline that platforms should not be addressing all these issues alone but should allow researchers, civil society and – if applicable – governments to support them in identifying and addressing risks on various levels. However, as with any attempt to regulate communication, especially regulators but also the stakeholders supporting them, are faced with a difficult balancing act between ensuring a healthy information environment and infringing on individuals’ right to free speech.

How does it relate to systemic risk and data access?

Art. 34(1c) clearly considers “any actual or foreseeable negative effects on […] electoral processes” as an example of systemic risk, which means trying to identify, detect and understand phenomena related to it is an unambiguous basis for data access requests based on DSA Art. 40. A significant part of this research (like the identification of coordinated inauthentic behaviour, or the tracking of moderation decisions) could already be conducted using public data, but other research (for example about algorithmic interventions or internal processes) requires non-public data. Acknowledging that the delegated act on non-public data access, the draft of which we have discussed above, will likely come into force in summer 2025 at the earliest, the Commission has published Guidelines on the mitigation of systemic risks for electoral processes (see points 29 and 30) this April: while not an enforceable claim, the Commission will positively evaluate VLOPs that “provide free access to data to study risks related to electoral processes” not only based on Art. 40(12) DSA but also using “additional and tailor-made tools, or features, including those necessary to study and scrutinise AI models, visual dashboards, additional data points being added to existing tools or the provision of specific datasets” to enable swift adjustment of “mitigation measures in relation to electoral processes”.

Other Risks | Other News

But we’re not done yet! There has also been a set of developments related to the DSA in general that we would like to quickly bring to your attention, in a section we’re calling

DSAddendums

- In early October, the German DSC, the Federal Network Agency, approved the first German trusted flagger. The case was directly sensationalised mainly by right-wing media to draw into question the reliability and influence of trusted flaggers and the DSA in general, leading the DSC to clarify that “neither trusted flaggers nor the Federal Network Agency decide what is illegal.”

- The European Commission has sent out a few requests for information to…

- The Commission has also opened formal proceedings against Temu, suspecting that the online marketplace is in violation of the DSA with regards to “the sale of illegal products, the potentially addictive design of the service, the systems used to recommend purchases to users, as well as data access for researchers.”

- The Commission has also laid down templates concerning the transparency reporting obligations of providers of online platforms in an Implementing Regulation. This means we will see the first transparency reports with harmonised format, content, and reporting periods in the beginning of 2026. Great news for anyone who wants to easily compare the data submitted by platforms to the DSA Transparency Database to their transparency reports.

Talking about reports, the publication of the first risk reports conducted by VLOPs are due this month. We’ll definitely take a closer look at them for you in our next newsletter.

Until then, keep asking for data access.